WORD PROCESSOR: HIGHLIGHTS FROM THE COLLECTION

February 9, 2015

Serios Matters

Karen Gregory

If you have ever written a word, you realize that it requires a certain type of labor. One must, to some degree, focus the mind, allow the whisper of thought to occur, and then move the muscles in your body to align these processes and actually manifest those thoughts and feelings through gesture. When we consider what we are doing when we write, the entire project falls nothing short of magical. Although note that I did not say "magic." Any writer knows that while the process is filled with tricks of the trade, words do not appear from nowhere nor do they appear without effort. For many, the line between effort and torment is notoriously thin. Who among us has not wished to circumvent the process entirely, but yet still produce those magical words? Who has not wished for the mind to "speak" directly to the page, meaningfully imprinting their own thoughts, feelings, and visions to the blank space? I suppose we believe that such an immediate and direct transfer would alleviate the struggle to make meaning.

Perhaps it is a bit of this desire for the alleviation of struggle that we see fueling the development of technologies like Google Glass, which while not technically a medium of writing, nonetheless attempt to re-script the world via a synthesis of mind, body, and machine. In a fantasy of a world-to-come, bridging the presumed gaps between mind, body, and machine results in a new, unfaultable empiricism. The fantasy desires a world of direct, "unmediated" communication. This is really nothing sort of desiring the presence-ing or manifestation of the ineffable, which we somehow imagine is a labor-free process.

Thankfully, The World Of Ted Serios: "Thoughtographic" Studies of an Extraordinary Mind (1967) by Jule Eisenbud, M.D. stands to correct this fantasy. Here, we meet a curious man named Ted Serios, who, if we are to believe Eisenbud and his reporting, has the capacity for transferring thought and vision directly to Polaroid film. Serios referred to his work as "thoughtographic" photography and the images that he produced throughout the 1950s and 1960s (his last image produced was in 1967. The image was of a curtain, which Eisenbud and others interpreted to mean the "curtain had fallen" on Ted's talent) resulted in a series of enigmatic, yet nonetheless fascinating images. Eisenbud, who was a practicing psychiatrist in Denver, Colorado and paranormal researcher, met Serios through the insistence of other paranormal researchers who felt that Serios could offer the paranormal field the long sought after gold standard of reproducible results. Despite Eisenbud's initial hesitation, he would go on to become both scientific researcher of Serios' powers, as well as documentarian and archivist of the visual artifacts produced. Serios' images are often of buildings or architectural shapes and, in many cases, they are too blurry to provide any easy image, but it's worth taking a moment to tour the images before you continue to read. While many of the photos contain a discernable image, there is also a considerable need for some apophenia if one intends to follow the story of Ted Serios.

Eisenbud writes of thoughography as a man with his feet in two different worlds, that of psychiatry and that of paranormal research, and The World Of Ted Serios spends a considerable amount of time trying to convince the reader that Eisenbud is both a reliable and legitimate narrator and that what we are about to witness is not a hoax. While obvious questions such as "why would this be possible?" arise immediately, the great white whale for the majority of the book is the legitimate proof of Serios' abilities. As Eisenbud writes, there is no dipping in the waters of paranormal research and by taking Ted as a research subject he's entered directly into the question of his own authority and legitimacy. The great legitimacy test, however, is rather tiresome and Ted, at many times, is the rather unruly subject, tormented by his own hit or miss abilities to produce images.

Serios, we discover, is a man with an alcohol problem and a sad past. He is a former bellhop who left school after the fifth grade and who may have suffered from traumatic abandonment. As Eisenburg accounts, he slept in his parents' bed until the age of eight when he was displaced by the birth of twins. Serios suffered recurrent nightmares about earthquakes or being pursued by a male authority figure. These nightmares persisted until he began his experiments with thoughtography, but they were promptly replaced by nightmares of being chased by a camera, "shaking as if in anger, its malevolent eye glaring at him from a fully extended bellows" (299). According to Eisenbud, Serios developed his thoughtographic abilities in the mid 1950s when a coworker discovered that Serios was a easily hypnotized subject. Under hypnosis, Serios was guided to explore the concept of seeing at a distance or "traveling clairvoyance", through which a medium attempts to mentally travel to other locations and have a look around. Through these sittings Serios became taken with the idea of finding hidden treasure and he was soon met with a "guide" from beyond. This guide was none other than Jean Laffite, the notorious pirate. With Laffite as a guide, Serios claimed to be shown the location of various hidden treasures (Eisenbud writes that Serios always maintained that there is a cove on an island off the coast of South Africa that contains Laffite's booty.) It was during his time "traveling" with Lafitte that a companion gave Serios a Polaroid camera so that he might better record these secret treasure maps. Sadly, Serios and his presumed talents were not met with the riches, fame, and glory he might have preferred. On the contrary, he developed a debilitating nervous condition and his attempts to disclose his work with camera were met with ridicule.

By the time that Eisenbud met Serios in 1964, Ted seemed to have made peace with his "powers", but he was nonetheless living a meager and estranged life. While the two seemed to have generated a working friendship, the book is a documentation of the trial and tribulations of the rather ill-fated pair. In order to "work", Serios demanded that he drink steadily and heavily and his dramatic process for producing the elusive thoughtograph was often punctuated by great commotion, failure, and naps. While the duo attempted several different configurations for creating the thoughtographs, the basic set up for Serios (in various stages of undress) to hold a polaroid camera in his hands or on his lap and employ a small "gizmo", which was a rolled up tube of black photo paper, to "focus" his psychic "energy" into the camera. Serios would then go into a state of intense concentration, "with eyes open, lips compressed, and quite noticeable tension of his muscular system. His limbs would tend to shake somewhat.... His face would become suffused and blotchy, the veins standing out on his forehead, his eyes visibly bloodshot" (25.) Cleary, whether hoax or not, Serios put on quite a performance.

Often these performances would result in what Eisenbud refers to as a "blackie" or a "whitie." Blackies were completely underexposed images that produced a fully black Polaroid, where whities were completely blown out white images, which would have technically been almost impossible to create given the lighting conditions. When Ted was "hot", however, he would produce dream-like images, often of buildings, street scenes, buses, or space rockets. Images of people seem to be absent from Serios' visual gallery. In his initial meeting with Eisenbud, Serios did indeed produce, after several failed attempts, an image of a marquee sign that read "Stevens." Eisenbud and his assistants recognized this sign as belonging to a former Hilton restaurant. It was sign that had not existed for more than thirty years. As we delve deeper into their relationship, we also learn that this sign has personal significance for Eisenbud as "Stephens" is the name of close, medical colleague. Eisenbud will eventually come to believe that Serios' images are not only visual images, but forms of communication that speak in the condensed language of dreams.

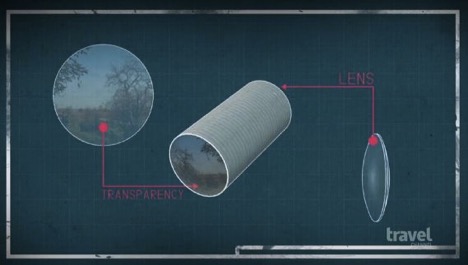

Inevitably, Serios and Eisenbud attracted several skeptics, particularly around the use of his gizmo, which was seen to be the obvious source of Serios' ability. James Randi and others speculated and subsequently proved it would have been possible for Serios to create these dreamlike images with the use of a small transparency placed at once end of the gizmo.

Serios, however, often submitted himself and his process to methodological constraints. He was stripped at times, placed in a Faraday tank, and often asked to produce a "target" image or an image that he had no knowledge of and that was sealed in a envelop. Serios did indeed produce "hits" under these conditions.

The manipulation of film always invites comparisons with the histories of paranormal and Spiritualist photography—a history replete with fraud and fakery—and Serios' work is yet another chapter in the ongoing desire to "capture" psychic ability in a medium that we assume provides empirical proof. Surprisingly though, discussions of the Polaroid as Serios' chosen medium are missing from Eisenbud's book. We are introduced the basic mechanics of the film and the camera, but the book never takes up the questions of "why Polaroid film or why this medium?" Rather, we find Eisenbud engaging in rather long-winded analyses of the symbolism of the Serios' images and the manner in which they may or may not be communicating. Eisenbud devotes a considerable amount of time to trying to develop a theory of the source of Serios' images, speculating that theories of the mind are far too limited and narrow to truly understand the ways in which mind and matter are entangled. For Eisenbud, the mind is a distributed mind, which can never be located firmly in the brain. Taking comfort in the reports of out-of body experiences, Eisenbud posits that it is possible that images Serios produced are a direct communication of an unbounded portion of Serios' mind. For Eisenbud, this accounts for why some of the text in the images has been misspelled, for example where the word should read "Canandian", Serios has produced "Cainada."

What I find most fascinating about The World of Ted Serios is the extent to which humans will go to enchant our own selves, particularly the mind, and in the midst of such enchanting we continue to search for proof of "our" ability. Rarely, do we stop to ask about the very metaphysics of matter or the modes of mediation that our enchanting projects obscure. Overlooking this question of matter always leads back to the same dull binaries—either Serios is a hoax or Serios is a miracle. Neither conclusion, in this case, is really satisfying. The enchantment that we seek, particularly through a form of empiricism that demands a perfect homology between the seemingly "ineffable" and its effects, will always fundamentally mistake technology as something neutral, something that does not itself participate in the project of communication.

And so, what do we learn from The World of Ted Serios? We learn that a rather sad and peculiar man may or may not have projected his thoughts onto film. If this was a hoax, it was indeed pulled off with great sophistication and that alone would be worth investigation. If it is true, then we will need a truly new materialism to account for whatever it is that pictures do indeed want.

Karen Gregory is a Lecturer in Sociology at the Center for Worker Education/Division of Interdisciplinary Studies at the City College of New York. Her work explores the intersection of labor, digital media, and contemporary spirituality. You can find her online at @claudiakincaid.

View The World Of Ted Serios: "Thoughtographic" Studies of an Extraordinary Mind in the catalog here.