WORD PROCESSOR: HIGHLIGHTS FROM THE COLLECTION

June 10, 2014

Tomorrow People

Rachel Levitsky

On the cover of Vol. 14 of Understanding Human Behavior: An Illustrated Guide to Successful Human Relationships is a lovely, young white middle-class hetero couple wearing 70s post counter-culture fashion. He: a worsted grey wide-label mod suit, long side burns. She: off-white long, lacy granny dress, wide-brimmed bone-white floppy hat over soft and loosely locked nut-brown hair. They stand on either side of a foreboding, ancient-looking stone cross, in what I surmise is a London cemetery. They are sort of facing each other; they cannot look at each other, however, because they are coughing so violently, and are still holding onto the very cigarettes that are killing not only them, but their ideal romance.

Is this a joke? An inside joke? Is it a conservative, right-wing condemnation of the counter culture and its confrontations with church and state authority, its poor hygiene, its detrimental ease with desire and addiction? Are these editors like the finger-pointing, nationalist, vitriolic, suburban members of the tribunal in Peter Watkins' 1971 film Punishment Park? Is this, with its nipple-removed nudity, an encyclopedia for libraries and schools? Or a sly ploy authored by the good folk at the Family Defense Council who also brought us such classics as the 1995 publication of The Pink Swastika?

From Punishment Park, 1971.

The writers of the 24-volume set are psychiatrists, dream and sleep experts, doctors of sexual medicine, lay-writers on brain and para-science. The beginnings of its chapters are somewhat sensationally scripted and conservative sounding, for example, this one about dropouts called "Dropout:"

They are regarded as loafers, spongers, parasites and potheads who are unwashed, long-haired and evil-smelling, who disfigure the social landscape and refuse to accept social responsibilities, to work, or to fight for their country. (1570)

Past these openings we find lines of reason more interested in the good scientific goal of uncovering human truths in order to make humans better.

The "Dropout" chapter continues:

The symptoms of the new social disease can be found in political, economic, religious, and technological shifts which have occurred in those years, and in the demands which these charges have made on individual citizens. (1571)

The tone is sort of patient, accepting and expansive, though this last quality is less apparent in the examples above or the ones I will quote below. The writing maintains a persistent anxiety about the hazards of 20th-century man in all his contradictorily speedy and slovenly object obsessions (food, gadgets, cigarettes, boobies, mass death), eager to figure out what can be done to save him by analyzing and understanding the scientific nature of even his most aberrant behavior.

Interestingly, Christine Doyle, the only woman on the set's eleven-person editorial board listed in the front matter of Vol. 1, is reportedly the first journalist on record to use the term "transsexual" when she titled her Observer article of April 28, 1974, "Transsexuals."[1] Which isn't to say that she, or any of the editors, was particularly radical or even progressive. One, Brian Inglis, ran the conservative English publication The Spectator until retiring to write for television and on extra-sensory perception. Another, the German-born psychologist Hans Jürgen Eysenck, a signer of the Second Humanist Manifesto, got himself into hot water (and a punch in the face) by supporting and extending hereditarian Arthur Jenson's research to show that variation in IQ between racial groups was biological not environmental (remember 1994's The Bell Curve?). Defensive of the scientism of his approach to intelligence and IQ, but horrified to be seen as maverick in his position, Eysenck put effort into publicly making a case that he was no fascist racist and that in fact his views were scientifically center. In 1994, in the wake of The Bell Curve controversy he was one of the 52 signers of the public statement "Mainstream Science on Intelligence," published in The Wall Street Journal, and in 1997 he published an autobiography, Rebel with a Cause, making the case that science, not politics, was the only and the pure cause behind his research and findings.[2]

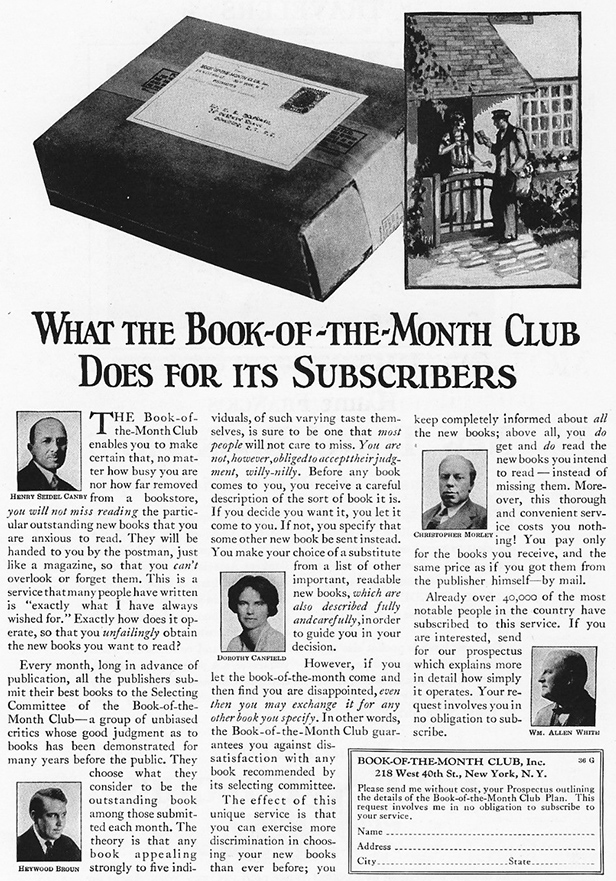

The series wants to be perceived as in touch with and invested in "the times," rather than hostile to or outside of the moment. Its direct marketing mode of distribution made the series an essential 70s collection; sold by the American outfit Columbia House, famous record club purveyors who took over the then-ubiquitous but now largely out-of-favor "10 for a Penny," "negative-option billing" technique from the Book-of-the-Month-Club.[3] It is a series packaged for popularity and approachability. Hence it is, as perhaps it must be, an illustrated guide.

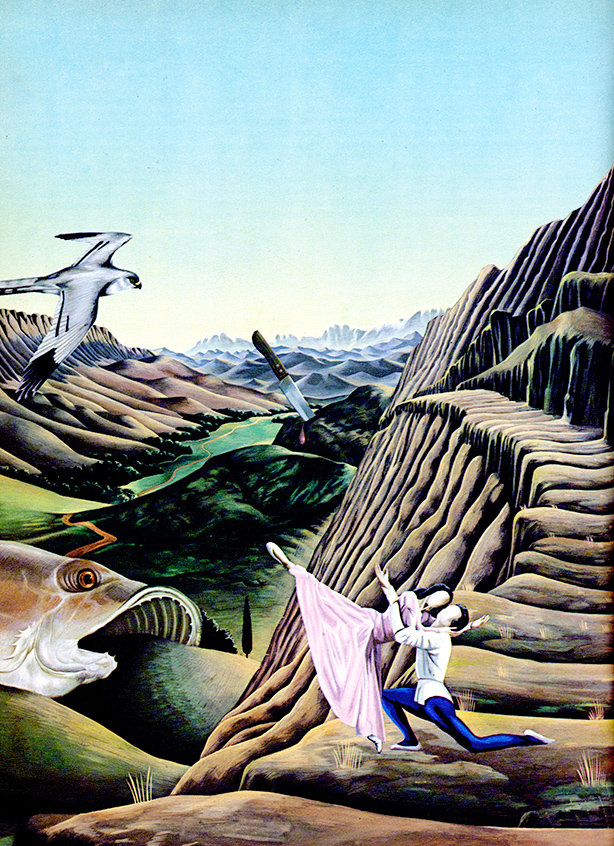

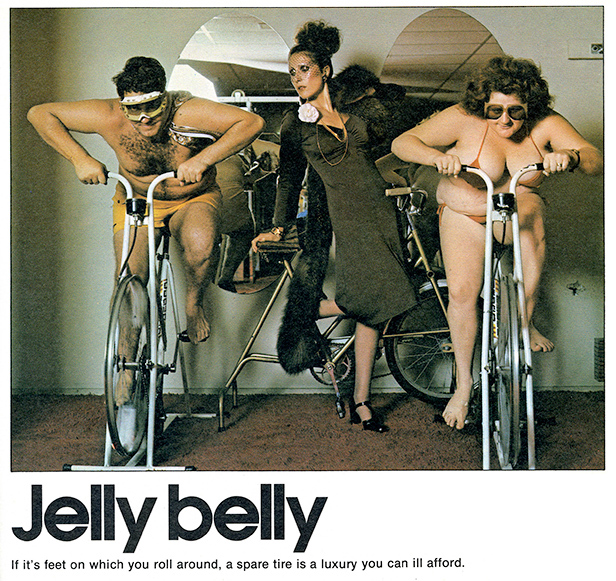

And the illustrations are almost always winners, one after the other, teetering on the edge of that which can be taken seriously and keeping me and those I've shown the volume to asking, "What?"

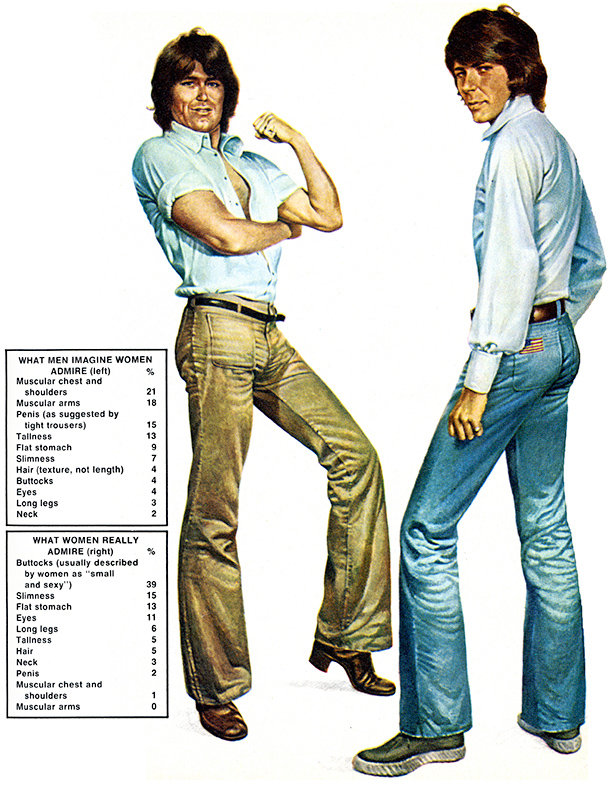

Much of the book is about body and body-image; the editorial board is most concerned with obesity, venereal diseases, ravages of the beautiful body, sexual perversity. A caption next to a full-page photograph of a man with a humongous hairy belly reads:

"Fat men are the product of the grab-all-you-can outlook of Western society where most people live to eat rather than eat to live. So it is that many people die from their greatest pleasure—food."

And here's another caption to a grotesque worker eating a sloppy sandwich:

"Chomp, chomp, slurp, burp, feed your face, forget your body, yum, yum, gets you quick a big fat tum."

But these psychologists are looking to systematize human behavior, not hate on the dropout, the "fatty," the suicide, the venereal slut and welfare mother, the juvenile delinquent, the aborter, the hoarder, the divorcee, the feminine puffer. They explain to us, and are confident that our intelligence quotient is sufficient to understand that young people, lazy fat people, sex criminals and women are not evil but understandably disillusioned by technocapitalist advance. The writers are learned, even and equanimous; they are here to disseminate their great learning. After a number of references to Freud and other psychological researchers of the era, they even quote Karl Marx, attributing his concept on Alienation as the causal factor of sex criminality.

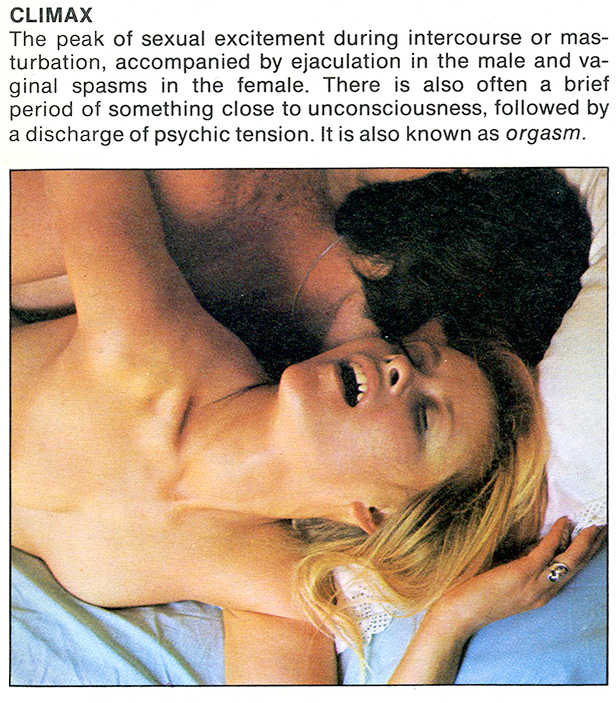

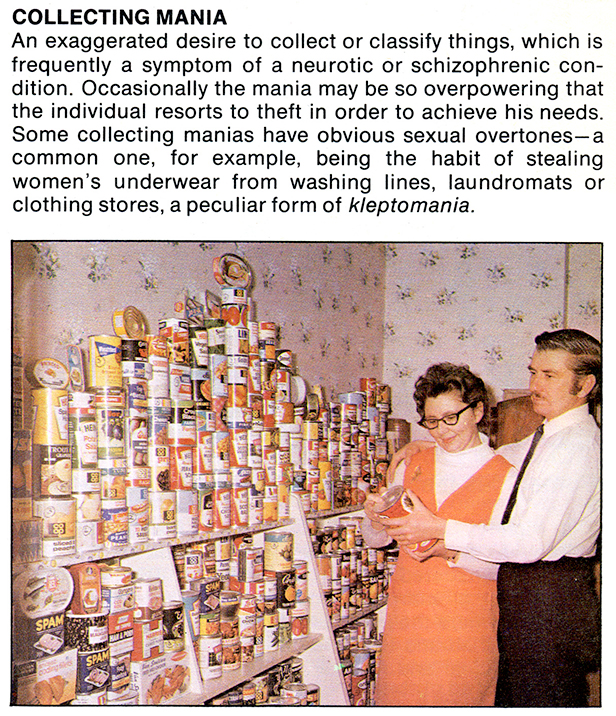

The series' chapters fall under headings that vary from volume to volume and which include themes such as: The Individual, The Family, Twentieth Century Man, Changing View of Man, Mind and Body, Sex and Society, Man in Society, Human Relationships, Question and Answer, Self-Improvement. My personal favorite, the A-Z Guide, progresses alphabetically through some of the 24 volumes, I can't be certain which:

I find these glossaries to be yet another expression of the editors' generosity and their desire to democratize the scientific mastery normally siloed within academia. Indeed, they are still very informative; I was excited to learn the names of things familiar yet unknown:

CICISBEISM

The practices whereby it is socially and legally acceptable for a married woman to take a lover.

CLOACA THEORY

A fanciful notion about childbirth. The cloaca is the rectum or back passage through which the feces are expelled. Children often believe that babies are born this way and in psychoanalysis this is known as the cloaca theory.

And I learned that "Certifiable" was actually "a legal term sometimes used in psychiatry." I was happily reminded of some old favorites: "Circular Thinking," "Chiromania" (chronic masturbation, term now out-of-date), "Coitus Interruptus," "Coitus Reservatus" (holding out to make it better), and the term for hoarding in 1974: "Collecting Mania," of course.

It turns out most of the editorial board, including Eysenck who moved to London from Nazi Germany in the 30s, are British, as was the actual publisher, a still-active book packager called BPC Publishing Limited. All of them are white. One of them, Christopher Evans (1931–1979) was a Welsh computer scientist who met his American wife at Duke University, wrote a book about Scientology, and was the science advisor for a British children's science fiction Thames TV show called "The Tomorrow People," which ran from 1973–79, and is partly available for viewing online. Here is Wikipedia's description of the show:

The Tomorrow People are the next stage of human evolution. They're teenagers blessed with the powers of teleportation, telekenesis, and telepathy. Together they protect Earth from alien threats, and work towards bringing mankind into its future, where communication with other worlds is the norm. But their gifts come with one limitation: They cannot kill, even to save themselves.

I purchased the digital version of the first and second episodes on Amazon. Besides the clunky aesthetics and video technologies obsolete and subpar even for their time, what seems most significant to me in these two episodes are the kinds of behavior that is symptomatic of emerging as a tomorrow person, or "TP" as they call themselves. Stephen Jameson has a sleep disorder, is hearing voices he doesn't yet know are telepathic communication, and is prone to sleep-walking, day-dreaming, fainting and the like. No question—and this is clearly the thinking of the doctor who interviews Stephen's mother after he has a fainting spell that lands him in the hospital—these are also symptoms of acute mental illness. Tomorrow Persons, with their advanced internal life unlocked by hypnosis and biotechnology, are responsible for the urgently needed rapid development toward the next species: "Homo Superior" (yes Nietzsche, yes David Bowie, yes Superman). Homo Superior represents a way out from the careen toward the grand personal, societal, political and environmental devastation laid plain on the streets, and on film screens of the early 1970s.

Stephen: I can feel it, what's happening?

Carol: You're becoming one of us! A tomorrow person.

Stephen: But tomorrow people, what are they?

Carol: The next development of the human race, Homo Superior, an improvement on Homo Sapien. The development of man hasn't just suddenly stopped, it's going on all the time. In the last 100 years everything has speeded up. The world has changed beyond recognition; human beings have changed with it.

Indeed, a survey of 1970s Hollywood movies tells a story of the unhinging of "society," or at least a loss of faith in that 19th-century notion that "society" exists as a hinge. See for example, Al Pacino's confidence that the police will screw him in Dog Day Afternoon (1975), or the serene, animal-loving Bruce Dern's willingness to kill his fellow pilots and commandeer the ship rather than blow up the last remaining forest in Silent Running (1972). Film after favorite film that I watch from that era, whether big or small, science fiction or neighborhood story, romance or post-apocalyptic comedy, contemporary or historical critique, follow the same basic formula: THX1136, The Landlord, McCabe and Mrs. Miller, A Boy and His Dog, Dog Day Afternoon, Chinatown, all start out bleak, stage a confrontation with the man, then end even bleaker.

But, in the world of Understanding Human Behavior, no such confrontation, and no bleak finale, need come to pass. We must only unlock the internal advances toward a Homo Superior using popularized psychology as our key. Human relationships will be more successful, the breakdown of society will be avoided.

According to Jürgen Habermas, "society" or the "public sphere" as we know it, was birthed in British cafés, German literary guilds and Parisian salons. Habermas notes that political, art, and literary criticism begins to be performed and formulated via "dialogue form" in a newly specialized public realm of private citizens, where what he calls "the experiential complex of audience-oriented privacy" makes its way through the market economy and into the "intimate sphere of the conjugal family." In other words, society happens when we perform our private selves in public, and our publicity becomes private. Alongside Michel Foucault's notion of biopower, which addresses the state apparatus' engagement in our sex, birth, death, and mental health, audience-oriented privacy is a good way to understand the optimism inherent in the work these volumes do to popularize psychological theory as an efficacious approach to the future of man.[4]

The editors of Understanding Human Behavior are not blithe. They are clearly concerned that this powerful force known as "society,"—a term they use repeatedly and with tremendous confidence in its power and agency as a force—is at risk. But, unlike the films of this special period that end sometimes suddenly and usually hopelessly by confirming that there is no outside, no way out from the grip of "the man," these guys and their one gal are holding out hope, asserting that "the man", he is us, inside us, were we to be equipped with this knowledge. Just like the tomorrow person Stephen Jameson, incoherently flailing, failing to comprehend the instructions and aid of the telepathic voices he needs in order to be freed from the evil Jedikiah's grip, 20th century readers teeter on the edge of receiving this critical communication, not only at individual great risk; at stake is the survival of the entire human community. These erudite, helpful expert-friends are telling us, warning us even, that escape from End Times is possible, and near. Society's potential future comes from inside each of us, as individuals, if we can only allow ourselves to understand.

[1]Jacques, Juliet. "Trans People Pronouns and Language." New Statesman. 16 Jan. 2013. Accessed June 6, 2014. http://www.newstatesman.com/lifestyle/2013/01/trans-people-pronouns-and-language

[2]The statement was written by Linda Gottfredson then signed by approached academics. A PDF of the statement, published on December 13, 1994 can be read in its entirety here. My favorite line in it is, "Whatever IQ tests measure, it is of great practical and social importance."

[3]There is so much to say about BOMC, including how this model was collapsed into record/cassette/8-track/cd/dvd distribution until the mid to late aughts. A good, clear summary can be found here.

[4]For Habermas on Society, see the Introduction or "Preliminary Demarcation of a Type of Bourgeois Public Sphere," in The Structural Transformation of the Public Sphere. Cambridge: MIT Press, 1991. (51) "Bio-power" is by now a widely referenced and perhaps mutated concept of Foucault's. My reading here comes from his 1976 The History of Sexuality: An Introduction. trans. Robert Hurley. New York: Random House, 1978. There, Foucault outlines an obsessive new regime of surveillance and control of families' sexual behavior during the Victorian era.

![]()

Rachel Levitsky is the author of two books of poetry, Under the Sun (Futurepoem 2003), NEIGHBOR (UDP 2009), a novel The Story of My Accident Is Ours (Futurepoem 2013), and several chapbooks including The Adventures of Yaya and Grace (Potes & Poets 1999) and Renoemos (Delete 2010). She is a member of the Belladonna* Collaborative, an officer in the Office of Recuperative Strategies (oors.net) and she is core faculty in a new MFA in Creative Writing and Activism at Pratt Institute. She is currently at work on several collaborations with poets and artists including Susan Bee, Simone Kearney, Marcella Durand, Ariel Goldberg, Christian Hawkey and Carla Harryman.

View Understanding Human Behavior in the catalog here, here, here, and here.