WORD PROCESSOR: HIGHLIGHTS FROM THE COLLECTION

June 30, 2016

Basic Radio

DeSales Harrison

A SCHEMATIC

is not a scheme, not devious, neither cockamamie nor cooked-up.

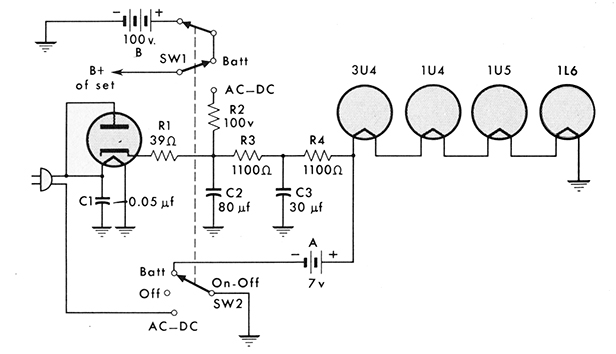

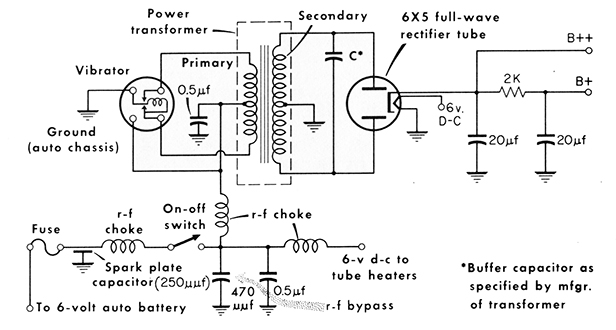

It is a diagram of a circuit, its connections and components laid out in two dimensions.

Obedient to strictest convention, it articulates the symbols for Resistor, Inductor, Capacitor in a network of wires and contacts.

The circuit has one job.

It either works or it doesn't.

This is the job description.

This is how its done.

The schematic is not a scheme.

It is perfectly intelligible, or it is not a schematic.

I don't understand them.

Perfectly ignorant of physics, calculus, material chemistry, I know I will never understand them.

I stare at a schematic, and I wonder what it would feel like to understand what I was staring at.

In the presence of the schematic, I stare and I wonder.

Here's what Death said:

"At evening you will be handed over to diminution, forgetting, and oblivion.

"In the interim, however, here on the imperceptible slope of middle age, you'll be passed from obsession to obsession, from enthusiasm to enthusiasm, without ceremony.

"In the catalog of those enthusiasms to which you have hitherto abandoned yourself, we note in no particular order: perfume, typewriters, Portuguese, Cy Twombly, knitting, Simone Weil.

"There are of course many more, enthusiasms all abandoned.

"A domesticated cultivar of madness, you say?

"Call it what you like. Call it middle age. Call it an ordinary disorder of the affections.

"Be that as it may, here's your next assignment: amplifiers."

What is he talking about? I can hardly hear him.

Schematics, I think. Isn't that what the flyer said? Electrical circuits.

But what kind of circuit?

Amplifiers, I think. Amplification.

What?

The signal drives the amplifier; the amplifier drives the speakers or the headphones; music fills your skull.

But what kind of amplifier?

A vacuum tube amplifier.

What is a vacuum tube?

A vacuum tube contains at least two electrodes, negative and positive, enclosed in a hard vacuum, sealed in an envelope of glass.

What does one look like, a lightbulb?

Like a lightbulb with a miniature tall building inside, a sort of skyscraper-in-a-bottle.

What do these electrodes do?

The electrodes (negative and positive), once powered, establish a high voltage charge between them, a potential for a strong flow of current.

So the tube passes a current, like a wire?

Yes, but unlike a wire, the tube is designed to shape or inflect that flow of current.

How does a tube shape or inflect the current?

Between the two electrodes, in the field of high voltage, a fence or screen of fine filament has been inserted.

Okay then, how does the filament screen shape the current?

As the louvers of a blind or signal lantern alter a beam of light, the screen can alter the beam of electrons, which is to say, the strong current between the electrodes.

What alterations does this screen impose?

It shapes the strong current to reflect the musical signal.

What is this signal?

The signal is the weak delicately fluctuating voltage from a phonograph, tape machine, radio, CD or mp3 player, the modulating voltage whose complex waveform transmits the music.

What happens to this weak signal once it is inserted into the strong current?

The weak fluctuating voltage inscribes itself on a strong fluctuating current —

Why?

— so that the strong current can impel the diaphragm of a loudspeaker to spirited movement —

Why?

— so that what had been a weakly fluttering voltage is now amplified, into a strong current, a current which the loudspeaker or headphone converts into sound waves, into the credible reproduction of sound —

Why?

— and music fills your skull.

The science defeats me, so I stare and wonder at the pages of the book, the instruction manual: Tepper, Marvin, Basic Radio, vol. 3, Rider Books, 1961.

It explains shortwave and AM transmission (mentions only in passing that exotic novelty, the FM signal) and illustrates each circuit component with a simple schematic.

The book is older than I am, published for radio hobbyists, ham operators, in the 1950s and 1960s, some of them teenagers, no doubt, but mostly middle-age men, I imagine, solitary riders of the nocturnal, long-range frequencies, practitioners of a hobby now nearly extinct.

How old would they be now? Many must be dead.

Lost in the past, adept in the necessary calculations, in Ohm's Law and Kirchhoff's Law, they understood then what I will never understand.

The schematic illustrations are perfectly clear, and yet for me (though I know the symbols for resistor, transformer, capacitor, inductor, and vacuum tube) perfectly opaque.

Perfectly opaque, therefore beautiful.

What I build are kits, the schematics and BOMs (bills of materials) devised by experts far away: Seattle, China.

I buy them from online businesses, bottlehead.com, diyaudiostore.com, twistedpearaudio.com, and seek advice in online forums, aware but only intermittently, of the irony of purchasing tube gear over the internet.

In the years following World War II, the vacuum tube, inefficient, expensive, and power-hungry, (in reality a kind of primitive switch) was rendered instantly and permanently obsolete by the cool-running, cheap, and efficient transistor.

Transistors started out tiny (compared to vacuum tubes) and only got exponentially smaller, vanishing in their millions, their billions, into the singularity of the microchip.

Skyscrapers packed with of stacked and networked vacuum tubes could not perform the calculations a single modern microchip can perform.

The internet is itself a network of billions of microchips.

Ordering my amp kits online is like ordering a carrier pigeon by satellite telephone.

Read through these instructions through before you begin, and familiarize yourself with the schematic on p.87.

Why?

Cut and trim a length of red wire 2" long, and attach (but do not solder) one end of the wire to plate choke terminal #6.

Why?

Attach and solder the other end to terminal 16L.

Why?

Solder the positive lead of a 3.3 μF capacitor to terminal 14U and the negative lead to 18U. DO NOT reverse the polarity of the capacitor.

Why?

When checking resistances with your multimeter, some readings may fluctuate wildly between very high values.

Why?

You have now completed assembly of the circuit.

Why?

The argument goes like this.

Tubes: they just sound better.

When you turn them on, they glow and warm up.

Likewise, the sound tubes produce is warm and incandescent.

By contrast, cool-running, efficient solid-state (transistor) amplifiers sound chilly and efficient, and who wants their music to sound chilly and efficient?

Turn the tube amp on (the one you assembled!) and let the tubes heat up.

Wait for the amber glow.

That is what the music is like, amber: sweet, clear, warm, golden, natural.

The tube amp: a technology preserved in amber.

Can you hear the difference?

You believe you can.

Why?

There is nothing like it, listening to a good recording through excellent headphones driven by a tube amplifier, an amplifier you built yourself.

Why?

I recommend you start with recordings of dead artists, say of Josef Szigeti or Jacqueline du Pré, or with a single label. Decca, for example made superb recordings in the Fifties. Consider also Mercury's Living Presence series.

Why?

Believe me, it is a kind of secular epiphany, if such a thing is possible.

Why?

In the glow of the tubes, in the amber suspension, you believe you can hear it, the living presence of the dead.

Why?

Believe me.

In English: the delicate difference between listening and hearing.

E.g. "If you listen, you will hear it."

E.g. "No matter how hard you listen, you cannot hear it."

You are listening to the music, yes, but you are also listening to your amplifier, to the tubes.

Can you hear it, the imperceptible difference they impart?

You believe you can.

Can you hear them, the voices of the dead, that weak fluctuating voltage made strong?

You believe you can.

Also: between looking and seeing.

E.g. "Look there, can you see it?"

E.g. "No matter how hard I look, I can't see it."

The schematic is a simplification, a universal hieroglyphic.

If it is not perfectly intelligible, it is not a schematic.

Looking you do not see. Listening you do not hear.

On the imperceptible slope of middle age, you stare and wonder.

DeSales Harrison teaches English at Oberlin College. His novel "The Waters and the Wild" is forthcoming from Penguin Random House.

View Basic Radio in the catalog here.